Ben Sargent, host of TV’s Hook, Line & Dinner, visits Miami in pursuit of the elusive snakehead fish, and shares insights about urban angling and sustainable species while eating at the city’s great seafood restaurants.

It’s just past dawn, and I’m standing, sopping wet and freezing cold, on a small bass-fishing boat in Plantation, Florida, a suburb about 30 minutes north of Miami. I’m with Ben Sargent, expert urban fisherman and host of the Cooking Channel’s Hook, Line & Dinner series. I’m utterly miserable, but Ben is unfazed. He keeps casting his line, hell-bent on landing a snakehead, the troublesome fish he has been after, unsuccessfully, for the past five years. “One just struck,” he shouts when the canal waters stir around his lure—but, upon reeling in an empty hook, he lets out an exasperated, guttural, “Oh, come on!”

After more than a hundred rain-soaked casts, Sargent finally pulls in a teensy snakehead, maybe eight inches long. He holds it up, full of pride: “I don’t care how small it is,” he says, “I finally got one.” Looking for a photo op, he continues to cast his line, aiming at driftwood and weeds. Then, suddenly, entirely by accident, he hooks a three-foot-long snakehead—one of the biggest he’s ever seen.

Ben Sargent angling for needlefish in Biscayne Bay. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

We aren’t even supposed to be on a boat, or in a suburb. Sargent and I have traveled to Miami to check out the many bridges and piers where you can drop a line and catch a fish within city limits. Our goal: to learn what it means to serve local, sustainable fish in a seafood capital like Miami, and then taste that fish at the restaurants that cook it best. But we’ve been sidetracked by what Sargent calls “the damned snakehead.” He had already dragged a New York Times reporter to a dank marsh near LaGuardia Airport in search of one (no luck!) and had gotten so frustrated chasing them in Maryland that he jumped into the water with a snorkeling mask and spear.

Originally from Asia, the snakehead fish has rapidly spread through US freshwater systems over the past 10 years and has the potential to destroy almost everything in its path. It is enough of a threat to local ecosystems that many states have made possession of the fish illegal. “I first became obsessed with the snakehead when one literally jumped into my boat. I dove on top of it with all my weight—I’ve never battled a fish with my bare hands like that,” Sargent says. “Hours later, on dry land, the thing started thrashing again, scaring me to death.”

Dressed in a plaid shirt and jeans, Sargent, 34, looks like he’s prepared for a fish skirmish at any moment. A serious outdoorsman, he somehow made a name for himself on the streets of New York as Doktor Klaw, an alter ego who wore a gold lobster-claw necklace and sold lobster rolls illegally, without a license. Now he’s hosting the second season of his TV show, for which he travels around the country, fishing for the local catch and cooking it up in local restaurants.

A native New Englander, Sargent is the most public face of a family of fishing and oceanography experts. “I’m almost the black sheep of the family,” he says. “I feel like they look at me and think, Why does Ben get to do all this stuff? We’re the ones who study it.” He’s not kidding: His stepsister, Leah Feinberg, is one of the world’s leading authorities on copepods, a type of minuscule crustacean; his brother, David, runs the Gloucester, Massachusetts, Shellfish Department; his grandfather, a former Massachusetts governor, was also the state’s head of fisheries; and his father, an environmentalist and author, wrote a book about the sea life of Cape Cod’s shallow waters. “My father can walk down the beach and tell you a story about every little thing he picks up, from shells to horseshoe crabs,” says Sargent. “The first time you hear it, it’s mind-blowing. The second time, you think, This man is amazing. The third time, you’re like, Does he know how to talk about anything else? And the answer is no.”

Ben Sargent tastes yellow jack ceviche with caviar and papaya at Miami’s Tuyo. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

Once we arrive in Miami, Sargent and I head straight to Garcia’s, a restaurant that has served local seafood for 46 years, much of it from its own fleet of fishing boats. We sit on the back patio, overlooking the Miami River, as commercial fishing vessels and party boats idle by. Sargent recalls the last time he was here, when the Garcia brothers taught him how to harvest spiny lobsters responsibly. “Their trap will rot out if it ever gets lost at sea, so the lobsters can escape,” he informs me, stabbing a hunk of grilled lobster tail with his fork and dunking it in drawn butter.

While the Garcias’ menu includes local catches like conch and grouper, there’s one clearly nonlocal fish: wild salmon, from Chile. “Why is salmon on a menu that focuses on Miami seafood?” Sargent wonders aloud. “I think we’ve developed a bad habit, where seafood restaurants think they have to serve salmon to make customers happy.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by chef Andrew Carmellini, who recently opened a branch of his New York City restaurant The Dutch in the sleek, breezy W South Beach hotel. It can be a struggle, Carmellini says, to balance his desire to promote lesser-known sustainable fish with pressure to serve the standbys. “It would be easy to put tuna on our menu, but I don’t want to,” he tells me. “Instead, I offer wahoo, which is tuna-like. People ask why we don’t just sell tuna instead of this funny fish that sounds like yahoo.” Some local specialties are also, happily, total crowd-pleasers, none more so than sweet stone-crab claws, on Carmellini’s menu through May. “Fishermen are required to throw the crab back after removing one or both claws,” Sargent tells me. “The crab ends up regenerating even bigger, stronger claws, so it’s more than sustainable.” I’m happy to be doing the crab a favor as I dig into the claw on my plate.

Ben Sargent and chef Norman Van Aken in the kitchen. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

Stone crabs aside, sustainable seafood issues are tricky, both for out-of-towners like Carmellini and for local chefs. Horacio Rivadero, the seafood-obsessed chef of Latin-inspired favorite OLA and the stylish new Dining Room, admits he’s often forced to make difficult decisions. “When a fisherman tells me he has lobster from Maine that’s sustainable, and Key West snapper that’s local but not sustainable, I have to choose,” Rivadero explains. “I think sustainable is more important.” But he has found seafood that fits into both categories, such as cobia, a tender, white-fleshed fish that’s farmed in the Caribbean. At the Dining Room, he serves it as a ceviche topped with grapefruit sorbet.

It’s nearly midnight by the time we leave. Before seeing us off, Rivadero’s staff gives us a tip: The best place to fish is Key Biscayne, an island off the southernmost point of the city.

The next day, we park under the Rickenbacker Causeway, the sweeping bridge that connects the mainland to Key Biscayne, and find a spot with a view of downtown Miami’s aqua-and-white high-rises. Next to us, several men are standing with rods and plastic buckets. Sargent unloads a camouflage rod bag loaded with five poles and a dangerous-looking spear gun. It feels a little like arriving at a duck hunt with a machine gun, but he explains that fishing methods vary so much from one location to the next that it’s best to come over-prepared.

Casting his line into the clear blue bay water, Sargent soon gets the attention of some slender, silvery needlefish. Hooking them, though, proves to be a bigger challenge. We can see their tweezer-like beaks chasing the lures, but they seem wise to the subterfuge, darting away without taking a bite. “These are the moments I love. When you think, I’m sure I can’t catch anything here. And the next minute, you have a 20-pound fish on your line,” Sargent says. Today, though, won’t prove so fruitful. We catch not a single needlefish.

Chef Norman Van Aken serves up Ben Sargent’s snakehead catch. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

Sargent is not deflated: He still feels the rush from reeling in the snakeheads. We bring them as a gift to Florida’s original celebrity chef, Norman Van Aken, whose new restaurant, Tuyo, comprises the top floor of the year-old Miami Culinary Institute. Van Aken has prepared us a stunning seafood lunch, and he has graciously agreed to cook up our catch. He and Sargent team up to clean the bigger snakehead, and after the flurry of scales settles, two pristine white fillets sit atop a cutting board.

Van Aken serves us custardy corn pudding studded with sweet Gulf shrimp, a Key West yellowtail-snapper fillet with spinach and silky mashed potatoes, and then the snakehead, cooked simply and served with lime wedges. It tastes amazing, like a cross between monkfish and swordfish, with none of the muddy flavor that’s common with freshwater fish. Seeing it on a plate, finally, gets Sargent thinking. “Can we call a snakehead local if it’s not native? Is it a sustainable fish? I don’t know—these terms don’t work for everything,” he says, then shakes his head and digs in, forgetting the complex argument for the moment. “It really tastes great.”

Tuyo, one of Ben Sargent’s Miami seafood restaurant picks. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

Open since 1966, Garcia’s is a Miami institution. Most of its seafood, including yellowtail snapper, spiny lobster and stone-crab claws, comes from its own fleet of fishing boats. 398 NW North River Dr.; 305-375-0765 or garciasseafoodgrill.com.

Last November, chef Andrew Carmellini—who grew up vacationing in Miami—opened this sister restaurant to his New York City location. Its menu features local seafood, such as the tuna-like wahoo. 2201 Collins Ave.; 305-938-3111 or thedutchmiami.com.

This warm and unassuming Miami Beach restaurant from Horacio Rivadero (also executive chef at OLA) feels like a true neighborhood spot; try the cobia ceviche with yuzu juice and grapefruit sorbet. 413 Washington Ave.; 305-397-8444 or diningroommiami.com.

Star chef Norman Van Aken prepares dishes like corn pudding with Gulf shrimp at his latest restaurant. It’s located on the top floor of the new Miami Culinary Institute, with sweeping views of downtown. Miami Dade College, 415 NE Second Ave.; 305-237-3200 or tuyomiami.com.

Star chefs reveal their favorite fishing spots.

Ben Sargent fishes in Biscayne Bay before joining chef Norman Van Aken for a snakehead tasting. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

View the original article here

Ben Sargent angling for needlefish in Biscayne Bay. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

Ben Sargent angling for needlefish in Biscayne Bay. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi. Ben Sargent tastes yellow jack ceviche with caviar and papaya at Miami’s Tuyo. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

Ben Sargent tastes yellow jack ceviche with caviar and papaya at Miami’s Tuyo. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi. Ben Sargent and chef Norman Van Aken in the kitchen. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

Ben Sargent and chef Norman Van Aken in the kitchen. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi. Chef Norman Van Aken serves up Ben Sargent’s snakehead catch. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

Chef Norman Van Aken serves up Ben Sargent’s snakehead catch. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi. Tuyo, one of Ben Sargent’s Miami seafood restaurant picks. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

Tuyo, one of Ben Sargent’s Miami seafood restaurant picks. Photo © Graciela Cattarossi.

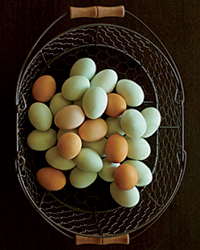

Fresh eggs from Natalie Coughlin’s small brood. Photo courtesy of Natalie Coughlin.

Fresh eggs from Natalie Coughlin’s small brood. Photo courtesy of Natalie Coughlin. Natalie Coughlin uses her Vitamix to make fresh almond milk. Photo courtesy of Vitamix.

Natalie Coughlin uses her Vitamix to make fresh almond milk. Photo courtesy of Vitamix.